Amitabh Bachchan has said that if ever asked about his caste by Census enumerators, his answer would be: Caste – Indian. That, of course, would do little more than stoke the media’s Bollywood feeding frenzy yet again. Shyam Maharaj is no Bachchan. Nor is his brother, Chaitanya Prabhu. But they and the followers of their fraternity are likely to throw up far more complex answers – and questions – if Census enumerators do finally pop that query on caste. “Our answer: we are ajaat. Here is my school leaving certificate to prove that. But you can write what you like,” Prabhu tells us at his house in Mangrul (Dastgir) village of Amravati district in Maharashtra.

Ajaat literally means people without caste. The ajaat was a bold social movement of the 1920s and ’30s that at its peak had tens of thousands of committed followers in what are present-day Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh. It was led by the colourful and eccentric social reformer Ganpati Bhabhutkar better known as Ganpati Maharaj. Chaitanya Prabhu and Shyam Maharaj are his surviving grandsons. Apart from the usual anti-liquor and anti-violence norms of such movements, Ganpati Maharaj threw in others. He attacked caste frontally. Many stopped idol worship at his call. He pressed for gender equality and even railed against private property. And, in the 1930s, he and his followers declared themselves as ‘ajaat’.

His inter-caste dining drive raised hackles in the villages he worked in. As one of his disciples P. L. Nimkar put it: “He would ask his followers from all castes to bring cooked food from their homes. This, he would mix up totally and distribute the mix as prasad.” Caste was his great target. “Inter-caste weddings and widow remarriage – that’s what he sought and achieved,” says Prabhu. “In our own family, from granddad to us, we married into 11 different castes, from Brahmins to Dalits. In our extended family there have been scores of such weddings.”

Ganpati Maharaj himself had such a marriage. He also “created the religion of ‘maanav’ (humanity) and opened the temple here to Dalits, offending the upper castes,” says Shyam Maharaj. “They filed cases against him and no one would touch his case. All the vakils here at the time were Brahmins.”

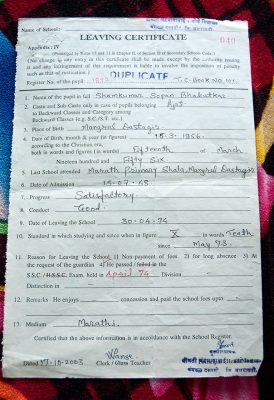

Chaitanya Prabhu (left) and Shyam Maharaj, the only surviving grandsons (in 2010) of Ganpati Maharaj, who led the anti-caste movement. Shyam Maharaj’s school certificate lists his caste as ‘ajat’ (misspelt , as is his name), but this is no longer an option

The movement waned over years, as some followers left on the caste issue, and with its Guru’s death in 1944. (He is buried at a community centre he built here decades ago, just opposite Prabhu’s house). Still, it remained known and respected for some time after Independence. “See my school leaving certificate,” says Prabhu, showing it to us. “As late as the 1960s, even the ’70s, we still got certificates calling us ajaat. Now, schools and colleges say they’ve never heard of us and won’t give our children admission.”

The surviving ajaat are not doing too well. Shyam and Prabhu just about make ends meet as petty agricultural traders.

Forgotten by the late ‘70s, the ajaat were re-discovered some years ago by Nagpur journalists Atul Pandey and Jaideep Hardikar. Their reports sparked a Maharashtra government move to help them. But that died with the exit of the one senior official who had shown interest in the matter.

Ajaat candidates can’t contest panchayat polls. Poll officials refuse to accept their forms – which state no caste. “Ajaat folk can’t get ration cards without a huge struggle,” says Prabhu. College admissions, scholarships and government jobs elude them for the same reasons. Other villagers won’t marry into these families now as their caste status lacks clarity. In short, the followers of a once proud anti-caste reform movement have been reduced to a couple of thousand people viewed as something like a caste themselves.

“My niece Sunaina could not get into college,” says Prabhu. “The college said: ‘we don’t recognise this ajaat. Bring us a proper caste certificate and we’ll admit her’.” His nephew Manoj, who did finally make it to college, says: “They treat us as an oddity there. There were no scholarships for any of us. No one there believes such a thing as ajaat exists.” A restless younger generation feels imprisoned by the past. Many of the ajaat, including Prabhu’s family, have faced the ignominy of having to trace out an ancestor whose caste could be clearly proven.

The last remaining traces of the ajaat –the group’s community centre in Mangrul (Dastgir) village of Amravati district

“Imagine our humiliation,” he says. “We have to take out caste certificates for our children.” Not easy, given the generations of inter-caste marriages these families have seen. And even the ledger of the village kotwallists them as ‘ajaat.’ Some have had to trace a great grandfather whose caste could be established. “To recover and rebuild those old records is a horrible job,” says Prabhu. “The authorities suspect us of concealing things and faking our caste. And it hurts us like anything to make these caste certificates. But without them our children are truly stuck.” Sadly, they had no choice but to trace out the caste origin of anti-caste crusader Ganpati Maharaj himself. That was needed for his great-grandchildren.

Quite a few of the remaining 2,000 or so ajaat gather at that community centre in this village in November each year. “Now there is only one such family we have contact with in Madhya Pradesh,” says a glum Prabhu. The rest are in Maharashtra. “Only 105 are formally registered with our body, the Ajaatiya Maanav Sanstha. But far more than that come to our annual meeting. However, consider that we once had 60,000 members in this movement.”

“We need a much more comprehensive survey of caste than the mere introduction of a question in the Census will permit,” says economist Dr. K. Nagaraj (formerly with the Madras Institute of Development Studies) who has worked on the subject. “That we need caste data is beyond doubt. But we need that data in a frame that captures the huge diversity, location-specific nature, and the many other complexities of caste. A single question in the 2011 Census will not achieve that. This is perhaps a job for the National Sample Survey and its team of trained investigators with much advance preparation.”

So what happens if that enumerator does come around to your house with the question on caste? “Believe me,” says Prabhu, “It will confuse him. I think they should create a different category in the Census for people like us. We must declare who we are. We have fought against everything that stands for caste. But in this society, caste is in everything.”

Originally published in The Hindu